In summary: To teach spelling to primary or elementary-aged students, you should:

- Strengthen their ability to commit words to memory

- Expand their lexical store (the number of words they know)

- Develop their linguistic understanding (why words are spelled in a certain way)

Spelling is a complex subject to teach. While it’s tempting to think auto-correct and other spelling software will solve all of our problems, the reverse is true. The ever-changing demands of communication in the 21st century require greater flexibility than any other time in history. It’s never been more important for students to learn to spell.

As the demand for quality of communication and literacy grows, the ways we teach spelling to students must adapt. To help teachers deliver rich spelling instruction, we’ve devised a new pedagogical method: The Lexical-Linguistic Approach.

But before we introduce it, let’s run through the common problems we face in our classes:

The challenges of teaching spelling

Dealing with spelling myths and misconceptions

It’s commonly thought that spelling is a fixed ability or a genetic trait and it’s dependent entirely on reading ability and memory.

In reality, spelling is a skill that can be learned, must be taught explicitly, and requires more than a good memory to be properly understood.

Teacher confidence in spelling knowledge

While most educators have above average literacy skills, teaching spelling effectively requires deep pedagogical content knowledge. The way spelling was taught in the past has not adequately equipped some teachers with the depth of knowledge they require to teach spelling to the next generation.

Insufficient time to deliver proper instruction

In an increasingly crowded curriculum, teachers have less time to focus on each subject. Spelling can easily become a casualty in the fight against time. It’s frequently given a reduced focus in the larger subject of literacy and ends up with less attention than it deserves.

Students can’t hold onto their spelling knowledge

The ‘Friday’s Test, Monday’s Miss’ phenomena showed that students excelled at remembering how to spell words for tests but failed to retain the information after the tests were over. This is due to the perfect storm caused by insufficient time and using memory as the primary (and sometimes only) spelling strategy: we lack the time to teach in-depth spelling and are forced to rely on short-term memorisation techniques. This learning isn’t sticky and it shows.

Students can find spelling boring

When you’re relying on memorisation to teach spelling it reinforces the idea that spelling is an innate ability – so our students think ‘what’s the point?’ and find their practice and fluency tasks seem disconnected, purposeless and repetitive.

What are the spelling milestones for students?

As with all learning areas, students progress at different rates and may follow a range of learning pathways. Yet many academics have presented theories on the stages of development of spelling acquisition.

There is a risk that an overemphasis on the stages of development can limit students’ exposure to rich connected learning and a wide range of skills and knowledge. However, the stages can provide a guide to the type of instruction that individual children, as well as groups of similar children, most need at each stage of development.

As such, the milestones of development follow very loose and overlapping age bands to allow for variations in the rate of skill acquisition. The progress from one stage to another is not linear, nor is it implicit. Progress demands explicit teaching and revision.

Pre-school (age 0–5)

Children write a string of letters or marks without any understanding of the correspondence between letters and sounds. Depending on their home and preschool experience, some children may make some progress into the next stage.

The first 3 years of school (age 5–8)

Spelling instruction targets the development of phonetic understanding. The focus is on helping students become more consistent in their use of conventional spelling and begin to remember a small bank of high frequency words.

Children typically:

- develop phonemic awareness

- learn about sound–letter relationships

- learn that language is broken into words

- spell phonetically

- use invented spelling

- leave out vowels

- learn to spell their name

- use environmental print to assist their spelling

- spell simple, common CVC (consonant-vowel-consonant) words

- reverse letters.

The next 3 years of school (age 7–10)

Spelling instruction moves away from a strong reliance on phonology and focuses more on the acceptable letter patterns of the English language (orthography).

Children typically:

- spell words they read and use frequently

- break words into syllables

- begin to spell unknown words

- start to use rhyme to spell words

- find and correct simple spelling errors

- use sources around them for spelling

- consolidate understanding of how words are formed.

The next 3 years of school (age 9–12+)

Spelling instruction continues to focus on acceptable letter patterns (orthography) but also focuses more on morphology as students add prefixes and suffixes to root words, become more confident in spelling multisyllabic words and investigate the origins of words.

Children typically:

- continue to develop visual memory

- become increasingly accurate

- learn how to form compound words

- spell words made of many syllables

- develop personal spelling lists for their writing

- learn spelling rules

- develop an understanding of the origins of words

What are the elements of spelling?

Spelling knowledge is made up of 5 distinct elements:

Phonology

[phono‘sound’ +-logy‘study’]

Phonology is concerned with the smallest units of sound (phonemes). It is the understanding of sound in words; read and heard, spoken and written. Teaching phonology in spelling focuses on developing the skills to identify sounds through segmenting and syllabification and represent them using letters (graphemes).

Examples of phonology activities include:

- Phonics knowledge (segmenting and blending)

- Matching sounds to graphemes (eg. Elkonin boxes)

- Finger spelling

- Onset and rime

Orthography

[orthos‘correct’ +-graphia‘writing’]

Orthography is concerned with the common letter sequences and patterns that are acceptable in the English spelling system. A rich orthographic knowledge allows students to make and apply rules and generalisations as well as develop visual sensitivity to acceptable letter patterns.

Examples of orthography activities include:

- Applying rules

- Making general statements

- Exploring alternative letter patterns

- Identifying acceptable letter patterns and spellings

Morphology

[morpho‘shape’ +-logy‘study’]

Morphology is concerned with the smallest units of meaning (morphemes) within words. Instruction aims to develop knowledge of morphemes including prefixes and suffixes and the ability to manipulate and understand morphemes in words. A rich morphological knowledge is vital to allow writers to use known words in different parts of speech, person and tense.

Examples of morphology activities include:

- Word building (prefixes and suffixes)

- Compound word activities

- Word fact files

- Exploring word meanings

Etymology

[etymos ‘true sense’ +-logy‘study’]

Etymology is concerned with the origin and history of words – where they came from, their pronunciation, and their meaning. Instruction aims to provide knowledge of these origins and how they inform spelling and meaning. A rich etymological knowledge is vital in storing words in a meaningful system and improves vocabulary.

Examples of etymological activities include:

- Identifying word families (tricycle, tripod, trident, triple)

- Identifying letter patterns from other languages

- Constructing meaning from etymology (photo (light) + graph (drawing))

- Building vocabulary

Lexical store

The lexical store is an ordered and reliable store of words and word knowledge. It’s where we store how words are spelled, what they mean, and their relationship to other words and meanings.

Efficient retrieval of a reliable lexical store reduces the cognitive load in writing tasks and allows students to focus on the complex task of expressive communication. It also provides a bank of knowledge that can be used to apply known spelling to new words.

Examples of lexical storing activities:

- Mnemonics

- Spelling bees

- Look, say, cover, write, check

- Word fact files

How do we teach spelling?

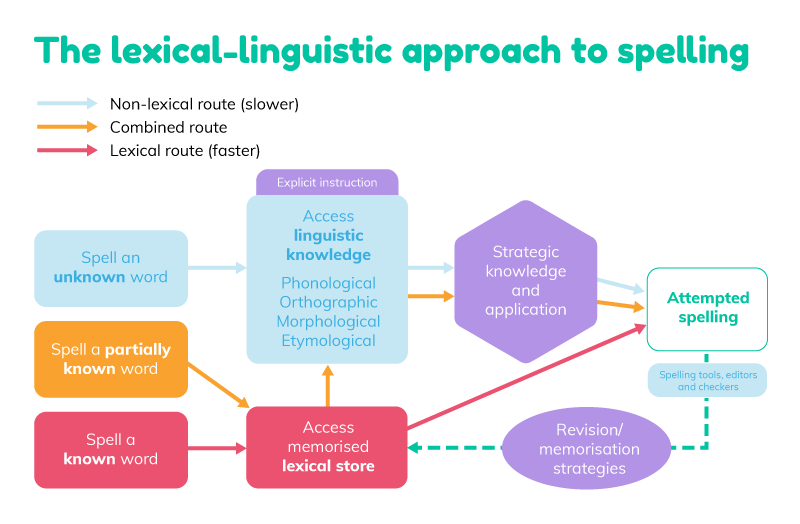

To help students become confident spellers we need to build their understanding of phonology, orthography, morphology and etymology, grow their lexical stores, and develop efficient memory and retrieval techniques. We’ve developed a new spelling approach that addresses these disparate elements into one method:

The Lexical-Linguistic Approach

The Lexical-Linguistic Approach gives students the tools and knowledge they need to make better attempts at spelling unknown words.

What do we mean by explicit instruction?

Explicit instruction is used to demonstrate concepts and build student knowledge and skills. Teachers show students what to do and how to do it and create opportunities in lessons for students to demonstrate understanding and apply the learning. In the Lexical-Linguistic Approach, we acknowledge the need to provide explicit instruction in each component of effective spelling; showing them how it’s done, what it means, and how they can do it themselves.

What do we mean by strategic knowledge and application?

After students have an understanding of phonology, orthography, morphology and etymology, they’re able to apply the learning to spell a word they haven’t encountered before. For example:

A student learning to spell the word infinity for the first time may need to draw on:

| Phonology | The first 3 syllables can be spelled using common grapheme-phoneme correspondences i-n-f-i-n-i-t | ||

| Orthography | The final syllable makes the long /ee/ sound. At the end of a word, this is more likely to use the letter pattern ‘y’ or ‘ey’ | ||

| Morphology | The final /ee/ sound is also a suffix. The root word is ‘infinite’. To change this word from an adjective to a noun, we need to drop the ‘e’ and add ‘y’ | ||

| Etymology | The meaning of the word can be derived from the origins and meanings of its parts: in– ‘without’ + finite ‘end’ |

What are the benefits of the Lexical-Linguistic Approach?

The Lexical-Linguistic Approach makes spelling stick. Instead of the traditional methods of teaching students to remember how to spell certain words briefly, it provides them with the tools and reinforcement they need to understand words on a deeper level.

Further, while this improves students understanding and assessment scores in the short term, in the long term it creates better, more literate communicators.

Bonus: 3 spelling strategies for your classroom

Look, say, cover, write, check

This is a classic spelling strategy that helps students memorize spellings by both sound and visual appearance. Students:

- Study a word in its correct spelling

- Cover it up

- Write it themselves as they remember it

- Check their spelling against the original.

This is especially effective for drilling hard-to-spell words.

Mnemonics

Mnemonics are memory aids. They might be phrases, visuals, rhymes, or anything else that helps students recall a spelling pattern.

For example:

- Because: big elephants can always understand smaller elephants

- I would like a piece of pie

- Rhythm: rhythm helps your two hips move

- Words ending in ‘-ful’ are too full for the extra ‘l’

Challenge your students to come up with their own mnemonics. It doesn’t matter if they’re nonsensical – they’ll still help with long term memory.

Chunking

Chunking is the process of breaking words into individual building blocks that are easy to spell.

Encourage students to sound out the individual syllables in a word, and then have them spell those one at a time before putting them all together.

For example, ‘planting’ can be broken down into [pl] [ant] [ing].

Chunking makes the spelling process much less daunting for early learners, particularly with longer words.

Sources

Moon, B. (2014). The Literacy Skills of Secondary Teaching Undergraduates: Results of Diagnostic Testing

and a Discussion of Findings. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(12).

http://dx.doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2014v39n12.8