Scientific knowledge and scientific literacy are more different than they seem.

Our understanding of the world has never been better – for every advance we make into the digital world, for every discovery we make of the universe, we find thousands of questions left to answer.

These advances have affected more of our lives than we might give them credit for. We can look back to the invention of the printing press and how it completely changed the nature of society; how we spread information, who was able to get this information, and how education was completely reshaped around it.

Complex technology and scientific advancement are the backbone of the comforts and safety of modern living, and have far-reaching consequences that impact society, culture, politics, and the survival of life on earth.

Understanding the difference between scientific knowledge and literacy is the first step to understanding how vital scientific literacy is now, and will be, for generations to come.

Scientific knowledge

This is the easy part – scientific knowledge is ‘what you know’.

For instance, you might understand how and why the water cycle works, what part of a soundwave indicates how loud it is (hint: it’s the height!), how plants use the energy from sunlight to make their food on sunlight, and so on.

Having a strong basis of scientific knowledge is great; it helps you understand the world you live in.

Unfortunately, having all the facts does not make for a critical thinker – and this is where scientific literacy is king.

Scientific literacy

Our favourite definition of scientific literacy comes from Lombrozo (2015):

“Scientific literacy is the knowledge and understanding of scientific concepts and processes required for personal decision making, participation in civic and cultural affairs, and economic productivity”

Or even more simply put: understanding enough science to make good choices in life.

We can break down scientific literacy into 6 parts:

- Curiosity: asking, finding, or determining answers to questions derived from observations about everyday experiences

- Theorising: Describing, explaining, and predicting natural phenomena

- Discussion: understanding articles about science in the popular press and engaging in social conversation about the validity of the conclusions

- Informed: identifying scientific issues underlying national and local decisions and expressing positions that are based in scientific and technological understanding

- Critical: evaluate the quality of scientific information on the basis of its source and the methods used to generate it

- Evidence-driven: Posing and evaluating arguments based on evidence and applying conclusions from such arguments appropriately

(National Research Council 1996)

Example of scientific literacy in action

Scientific knowledge helps you understand omega-3 in fish is good for you, whereas scientific literacy helps you recognise that it’s not a miracle pill.

The ability to recognise pseudoscience is important – not to fight fake news or for the purity of truth – but because scientific claims can impact quality of life and health. Anything declaring it’s been tested or clinically proven should still face rigorous scrutiny.

And where do you get that level of scrutiny?

Scientific literacy!

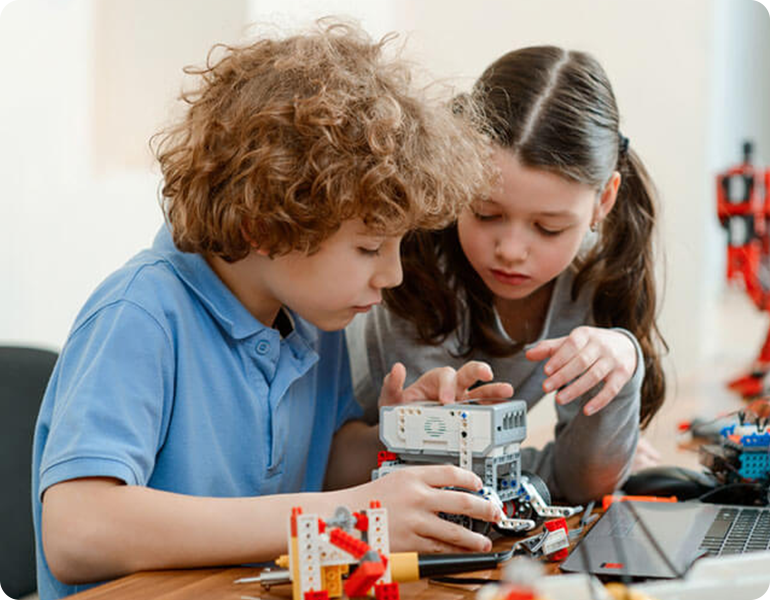

How to bring scientific literacy into the classroom

There are three tried-and-true methods to encourage scientific literacy in the classroom:

Use a variety of texts and media

Science is everywhere – there are endless (accredited) science news websites and blogs, videos, social media channels, as well as traditional textbooks and online journals to tap into. Programs like STEMscopes Science bring all of these into one comprehensive science learning platform that encourages kids to investigate, question and observe every day phenomena in a new way..

This has a web of benefits: kids are exposed to different angles on the same idea, they can gravitate towards the mediums they feel most confident learning with, you can almost be sure the information is up to date – and you’ll keep them engaged to the point of captivation.

Debate and discussion

Science progresses when old ideas are ousted with new information and better evidence – and you can’t do that without learning how to challenge assertions and present your own sources.

Including debate and discussion in classes can be done at almost any point during a lesson. You can start by assigning groups and asking them to assess the best way to find out if something is true, or mid-experiment ask them to vote on what they think the outcome will be and defend their position, or give them a hypothetical question at the end and ask students to come up with an angle to defend. Encourage them to use predictions, explanations, justifications based on some kind of evidence whether that’s from a valid source or from their own observations of everyday phenomena

Continual questioning and inquiry

We want students to do three things: notice –wonder why – hypothesise.

By getting kids into the practice of observing the world around them, questioning the why’s and how’s of natural phenomena, and trying to make sense of them using their knowledge and research, you’re creating critical thinkers.

It doesn’t have to be ground-breaking, it can be as small as noticing some trees leaves change to the season but others don’t, or that a compass doesn’t work properly when it’s close to a magnet.

This is a core part of STEMscopes Science 5E+IA model – a scientific model designed to support, strengthen and enhance scientific literacy in students.

Need help teaching science?

We’ve got you covered – check out how you can overcome the 4 Biggest challenges of teaching science to young learners.