Student motivation is an art and a science. Short-term encouragements like stickers, certificates, badges and rewards can be short-lived. Even familial praise and peer recognition only provide temporary boosts that fade with time.

The secret to enduring motivation is to inspire the idea that motivation is a choice.

Bookends of motivation

As we think about motivation in young learners, I see two very clear, and somewhat paradoxical, motivational needs.

On one hand, we want to encourage learners to engage in an activity or task that they are not inherently motivated to do. Perhaps they already dislike the subject or have a history of failure. Perhaps they have not yet made a connection to the value of this knowledge or skill. Perhaps they are caught in a mindset that tells them there is no point trying because they don’t have “talent” for this task. Or maybe they are just having a bad day! Regardless, we need to provide them with a motivating trigger to engage them and sustain that engagement long enough to be educationally beneficial.

On the other hand, we want to ignite a passion for learning, an enduring understanding of the value of learning and a mindset that shows the power of perseverance.

Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation

Traditionally, educators have relied on extrinsic motivators (rewards, praise, grades, punishment, shame) to encourage students to engage in learning, particularly those who are not inclined to be engaged. But the long-term goal is to develop intrinsic motivation where students are motivated by a sense of enjoyment, satisfaction and purpose, resulting in deeper, connected, sustainable learning.

‘Intrinsically motivated students are more engaged, retain information better,

and are generally happier.’ (Deci & Ryan, 2001, in Hanus & Fox, 2015).

There is significant evidence to suggest that extrinsic motivation can detract from the development of intrinsic motivation. Extrinsic motivation is often used for short-term gain but has a long-term detrimental effect on persistence, enjoyment and satisfaction. Despite these findings, extrinsic motivation continues to be used immoderately in all areas of education and at all levels.

The motivation continuum

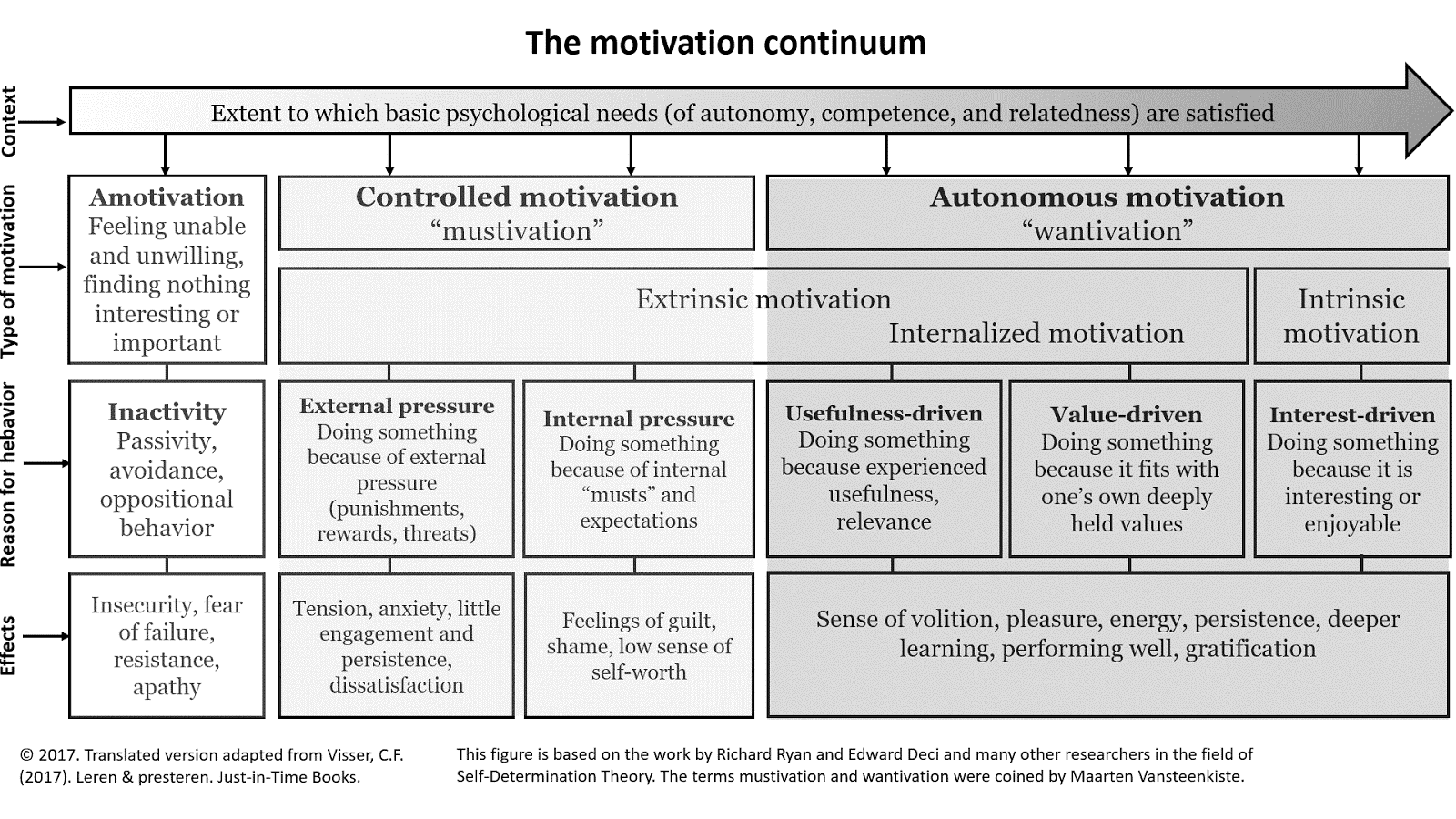

A continuum view of motivation is far more useful than a mutually exclusive intrinsic/extrinsic view. Visser’s (2017) model shows a continuum of controlled motivation to autonomous motivation with an increasing positive effect on learning and wellbeing.

Visser, C.F. (2017). The motivation continuum: self-determination theory in one picture. Retrieved from http://www.progressfocused.com/2017/12/the-motivation-continuum-self.html

This model seeks to position motivation as a measure of control versus autonomy. This approach is known as self-determination theory and is a highly effective lens through which to examine motivation. Visser, C.F. (2017). The motivation continuum: self-determination theory in one picture – original source.[/fusion_text][fusion_text]

Visser, C.F. (2017). The motivation continuum: self-determination theory in one picture – original source.[/fusion_text][fusion_text]

Self-determination theory

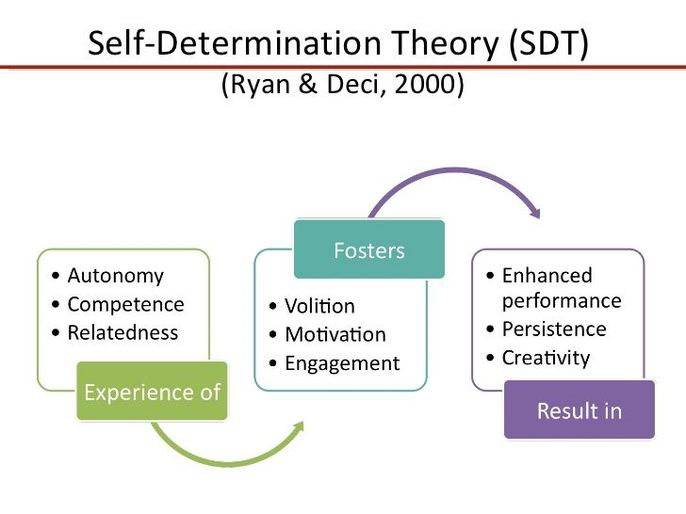

Edward Deci has spent four decades exploring motivation and concludes that “when people feel confident, related to others and a sense of volition, they will be positively motivated, and the positive consequences will follow” (Deci, 2017). Deci defines the connection of these three basic psychological needs – autonomy, confidence and relatedness – as self-determination theory which he believes has the potential to impact motivation, development and wellness.

Deci (2017). Self-Determination Theory [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/m6fm1gt5YAM.

Deci (2017). Self-Determination Theory – original source.[/fusion_text][fusion_text]

Deci (2017). Self-Determination Theory – original source.[/fusion_text][fusion_text]

Autonomy is key

The value of autonomy is enormous. Researchers have found that by adding an autonomous component to learning, regardless of any changes to the learning content, motivation is increased.

One study found that educational designers could “increase a motivation to keep working with the instructional material by easily implementing simple choices without changing the learning content” (Schneider, et al., 2018, p. 171). And the effect is even more pronounced among learners who have little independence in their learning environment. Among these students, “the effects of choice will especially help to raise a perception of autonomy”.

Educators and educational designers must constantly consider the level of autonomy students have in their own learning journeys. Motivation may be vastly improved by allowing students to make more choices about their learning.

Competence

Vygotsky’s (1978) notion of a ‘zone of proximal development’ has been ingrained in educational thinking for decades. It is the belief that students will learn best when the difficulty or complexity of their tasks is not too hard and not too easy – in a space where they can be challenged but autonomous.

Prolific researcher, John Hattie, prefers to use the ‘Goldilocks principle’ suggesting that the sweet spot for learning is work that is “not too hard and not too boring” (Hattie, 2015). This iteration taps into the value of competence as a motivational factor. If work is too hard or too easy, confidence is lost, or students become bored. Either way, motivation and engagement are also lost.

When thinking about promoting confidence, care must be taken not to misuse the fundamentals of growth mindset. Carol Dweck’s work in growth mindset is often misinterpreted into oversimplified and unhelpful messages to learners (Misinterpreting the Growth Mindset: Why We’re Doing Students a Disservice). An effective growth mindset does not blindly advocate blanket statements of positivity. Rather, it seeks to develop deep self-efficacy in students by preparing them for challenges, encouraging them to persevere and drawing on these successes to provide confidence for future challenges.

Relatedness

Learning is a social endeavour.

It is a basic psychological need to feel connected to others, to be a member of a group, to love and care and be loved and cared for. The need for relatedness is satisfied when people experience a sense of communion and develop close and intimate relationships with others (Broeck, et al., 2010).

A contributor to motivation is the sense of connectedness. This can be achieved through opportunities to collaborate and relate to teachers and peers by accomplishing group tasks or by receiving social support from others. However, opportunities for relatedness can also be deterrents as feeling pressured to engage in a collaborative task is not always accompanied by feelings of effectiveness and interpersonal connection. Educators must create environments of care, trust, equity and nurture while also considering each student’s ability and propensity to be socially connected.

In the digital age, students are highly experienced in online social connection and collaboration – often vastly more confident than in face-to -ace realities. These connections, and the associated confidence, create a clear conduit for opportunities to motivate through relatedness.

The role of curiosity

Researchers have also discovered the importance of curiosity in motivating learners in an intrinsically autonomous way. They found that it is essential to provide students with “learning materials that are informationally engaging (surprising or with the right level of complexity/learnability) in order to foster memory retention” (Oudeyer, et al., 2016, p. 94).

Findings suggest that learners’ brains are intrinsically rewarded by features like novelty or learning progress. They will spontaneously and actively search for these features and select adequate learning materials if the environment/teacher provides sufficient choices.

However, what triggers curiosity and learning will be different for different students. Therefore, continued choice, and the element of surprise will potentially maximise the level of curiosity.

Age is a factor

A final thought is that changes to motivation occur with age. A decline in motivation can be clearly seen in Hattie’s (2019) Jenkin’s Learning Curve which shows the dramatic drop in school enthusiasm.

Hattie, J. (2019). Building and Developing Assessment-Capable Learners [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/n3TJ6gvPisE

Research suggests that extrinsic motivation is prevalent in the early years of schooling, decreases up to 12 years old and stabilises after that point. However, it nevertheless remains systematically higher than intrinsic motivation throughout the school years. There is also a tendency to emphasise to students that schoolwork is important for their future but often without conveying that it can also be enjoyable (Gillet, et al., 2012).

There is a marginal improvement in the final years of schooling when a clear purpose, increased autonomy and stronger levels of relatedness with peers and teachers are prevalent.

Alternatives to extrinsic motivation

If extrinsic motivators are not effective, how can educators and educational designers engage and maintain engagement when students have not yet developed a deep interest that drives them to learn? What alternatives are there to the ever-present extrinsic rewards and structures of classrooms and educational products around the world?

- Provide learners with choices (autonomy),

- Ensure tasks are within the ZPD (competence)

- Create environments that allow for safe social connection in the learning process (relatedness)

- Foster curiosity using novelty, surprise and visible learning progress

We’re not always going to ignite motivation in our students, but that’s ok. Our role is to ensure that the classroom is a place where students are given appropriate autonomy, tasks are structured to improve competence and growth, students feel connected and curiosity is championed.

That’s what motivates us.

Motivate independent learning with our award-winning mathematics and literacy programs

Sources

Deci (2017). Self-Determination Theory [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/m6fm1gt5YAM.

Hanus, M. D. & Fox, J. (2015). Assessing the effects of gamification in the classroom: A longitudinal study on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfaction, effort, and academic performance. Computers & Education, 80(C), 152-161.

Gillet, N., Vallerand, R., & Lafrenière, J. (2012). Intrinsic and extrinsic school motivation as a function of age: The mediating role of autonomy support. Social Psychology of Education, 15(1), 77-95.

Hattie, J. (2019). Building and Developing Assessment-Capable Learners [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/n3TJ6gvPisE

Hattie, J. (2015) What Doesn’t Work in Education: The Politics of Distraction, London: Pearson.

Oudeyer, P., Gottlieb, J., & Lopes, M. (2016). Intrinsic motivation, curiosity, and learning: Theory and applications in educational technologies. Progress in Brain Research, 229, 257-284.

Schneider, S., Nebel, S., Beege, M., & Rey, G. D. (2018). The autonomy-enhancing effects of choice on cognitive load, motivation and learning with digital media. Learning and Instruction, 58, 161-172. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.06.006

Visser, C.F. (2017). The motivation continuum: self-determination theory in one picture. Retrieved from http://www.progressfocused.com/2017/12/the-motivation-continuum-self.html

Vygotsky, L .S. (1978) Mind in society. The development of higher mental processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.[/fusion_text][/one_full]